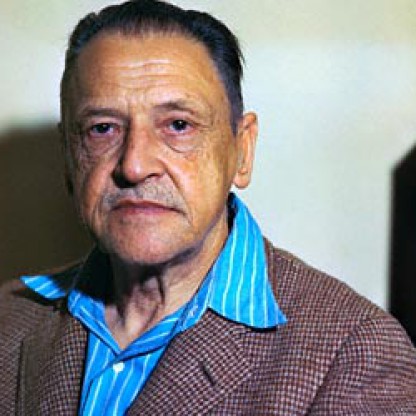

As per our current Database, Susan Sontag has been died on December 28, 2004(2004-12-28) (aged 71)\nNew York City, New York, U.S..

When Susan Sontag die, Susan Sontag was 71 years old.

| Popular As | Susan Sontag |

| Occupation | Writers |

| Age | 71 years old |

| Zodiac Sign | Aquarius |

| Born | January 16, 1933 (New York City, United States) |

| Birthday | January 16 |

| Town/City | New York City, United States |

| Nationality | United States |

Susan Sontag’s zodiac sign is Aquarius. According to astrologers, the presence of Aries always marks the beginning of something energetic and turbulent. They are continuously looking for dynamic, speed and competition, always being the first in everything - from work to social gatherings. Thanks to its ruling planet Mars and the fact it belongs to the element of Fire (just like Leo and Sagittarius), Aries is one of the most active zodiac signs. It is in their nature to take action, sometimes before they think about it well.

Susan Sontag was born in the Year of the Rooster. Those born under the Chinese Zodiac sign of the Rooster are practical, resourceful, observant, analytical, straightforward, trusting, honest, perfectionists, neat and conservative. Compatible with Ox or Snake.

In a print shop near the British Museum, in London, I discovered the volcano prints from the book that Sir William Hamilton did. My very first thought—I don't think I have ever said this publicly—was that I would propose to FMR (a wonderful art magazine published in Italy which has beautiful art reproductions) that they reproduce the volcano prints and I write some text to accompany them. But then I started to adhere to the real story of Lord Hamilton and his wife, and I realized that if I would locate stories in the past, all sorts of inhibitions would drop away, and I could do epic, polyphonic things. I wouldn't just be inside somebody's head. So there was that novel, The Volcano Lover.

— Sontag, writing in The Atlantic (April 13, 2000)

Sontag was born Susan Rosenblatt in New York City, the daughter of Mildred (née Jacobson) and Jack Rosenblatt, both Jews of Lithuanian and Polish descent. Her Father managed a fur trading Business in China, where he died of tuberculosis in 1939, when Susan was five years old. Seven years later, Sontag's mother married U.S. Army Captain Nathan Sontag. Susan and her sister, Judith, took their stepfather's surname, although he did not adopt them formally. Sontag did not have a religious upbringing and claimed not to have entered a synagogue until her mid-20s.

Remembering an unhappy childhood, with a cold, distant mother who was "always away", Sontag lived on Long Island, New York, then in Tucson, Arizona, and later in the San Fernando Valley in southern California, where she took refuge in books and graduated from North Hollywood High School at the age of 15. She began her undergraduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley but transferred to the University of Chicago in admiration of its famed core curriculum. At Chicago, she undertook studies in philosophy, ancient history and literature alongside her other requirements. Leo Strauss, Joseph Schwab, Christian Mackauer, Richard McKeon, Peter von Blanckenhagen and Kenneth Burke were among her lecturers. She graduated at the age of 18 with an A.B. and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. While at Chicago, she became best friends with fellow student Mike Nichols. In 1951, her work appeared in print for the first time in the winter issue of the Chicago Review.

At 17, Sontag married Writer Philip Rieff, who was a sociology instructor at the University of Chicago, after a 10-day courtship; their marriage lasted eight years. While studying at Chicago, Sontag attended a summer school taught by the Sociologist Hans Heinrich Gerth who became a friend and subsequently influenced her study of German thinkers. Upon completing her Chicago degree, Sontag taught freshman English at the University of Connecticut for the 1952–53 academic year. She attended Harvard University for graduate school, initially studying literature with Perry Miller and Harry Levin before moving into philosophy and theology under Paul Tillich, Jacob Taubes, Raphael Demos and Morton White. After completing her Master of Arts in philosophy, she began doctoral research into metaphysics, ethics, Greek philosophy and Continental philosophy and theology at Harvard. The Philosopher Herbert Marcuse lived with Sontag and Rieff for a year while working on his 1955 book Eros and Civilization. Sontag researched for Rieff's 1959 study Freud: The Mind of the Moralist prior to their divorce in 1958, and contributed to the book to such an extent that she has been considered an unofficial co-author. The couple had a son, David Rieff, who went on to be his mother's Editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, as well as a Writer in his own right.

Sontag was awarded an American Association of University Women's fellowship for the 1957–1958 academic year to St Anne's College, Oxford, where she traveled without her husband and son. There, she had classes with Iris Murdoch, Stuart Hampshire, A. J. Ayer and H. L. A. Hart while also attending the B. Phil seminars of J. L. Austin and the lectures of Isaiah Berlin. Oxford did not appeal to her, however, and she transferred after Michaelmas term of 1957 to the University of Paris. In Paris, Sontag socialized with expatriate artists and academics including Allan Bloom, Jean Wahl, Alfred Chester, Harriet Sohmers and María Irene Fornés. Sontag remarked that her time in Paris was, perhaps, the most important period of her life. It certainly provided the basis of her long intellectual and artistic association with the culture of France. She moved to New York in 1959 to live with Fornés for the next seven years, regaining custody of her son and teaching at universities while her literary reputation grew.

Sontag lived with 'H', the Writer and model Harriet Sohmers Zwerling whom she first met at U. C. Berkeley from 1958 to 1959. Afterwards, Sontag was the partner of María Irene Fornés, a Cuban-American avant garde Playwright and Director. Upon splitting with Fornes, she was involved with an Italian aristocrat, Carlotta Del Pezzo, and the German academic Eva Kollisch. Sontag was romantically involved with the American artists Jasper Johns and Paul Thek. During the early 1970s, Sontag lived with Nicole Stéphane, a Rothschild banking heiress turned movie Actress, and, later, the Choreographer Lucinda Childs. She also had a relationship with the Writer Joseph Brodsky. With Annie Leibovitz, Sontag maintained a relationship stretching from the later 1980s until her final years.

She became a role-model for many feminists and aspiring female Writers during the 1960s and 1970s.

It was through her essays that Sontag gained early fame and notoriety. Sontag wrote frequently about the intersection of high and low art and expanded the dichotomy concept of form and art in every medium. She elevated camp to the status of recognition with her widely read 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'", which accepted art as including Common, absurd and burlesque themes.

Sontag drew criticism for writing in 1967 in the Partisan Review:

In a 1970 article titled "America as a Gun Culture", the noted Historian Richard Hofstadter wrote:

In 1977, Sontag published the series of essays On Photography. These essays are an exploration of photographs as a collection of the world, mainly by travelers or tourists, and the way we experience it. In the essays, she outlined her theory of taking pictures as you travel:

At a New York pro-Solidarity rally in 1982, Sontag stated that "people on the left", like herself, "have willingly or unwillingly told a lot of lies". She added that they:

Sontag's mother died of lung cancer in Hawaii in 1986.

Sontag had a close romantic relationship with Photographer Annie Leibovitz. They met in 1989, when both had already established notability in their careers. Leibovitz has suggested that Sontag mentored her and constructively criticized her work. During Sontag's lifetime, neither woman publicly disclosed whether the relationship was a friendship or romantic in nature. Newsweek in 2006 made reference to Leibovitz's decade-plus relationship with Sontag, stating, "The two first met in the late '80s, when Leibovitz photographed her for a book jacket. They never lived together, though they each had an apartment within view of the other's." Leibovitz, when interviewed for her 2006 book A Photographer's Life: 1990-2005, said the book told a number of stories, and that "with Susan, it was a love story." While The New York Times in 2009 referred to Sontag as Leibovitz's "companion", Leibovitz wrote in A Photographer's Life that, "Words like 'companion' and 'partner' were not in our vocabulary. We were two people who helped each other through our lives. The closest word is still 'friend.'" That same year, Leibovitz said the descriptor "lover" was accurate. She later reiterated, "Call us 'lovers'. I like 'lovers.' You know, 'lovers' sounds romantic. I mean, I want to be perfectly clear. I love Susan."

In "Sontag, Bloody Sontag", an essay in her 1994 book Vamps & Tramps, art and cultural critic Camille Paglia describes her initial admiration and subsequent disillusionment:

Ellen Lee accused Sontag of plagiarism when Lee discovered at least twelve passages in In America (1999) that were similar to, or copied from, passages in four other books about Helena Modjeska without attribution. Sontag said about using the passages, "All of us who deal with real characters in history transcribe and adopt original sources in the original domain. I've used these sources and I've completely transformed them. There's a larger argument to be made that all of literature is a series of references and allusions."

In an interview in The Guardian in 2000, Sontag was quite open about bisexuality:

Sontag received angry criticism for her remarks in The New Yorker (September 24, 2001) about the immediate aftermath of 9/11. In her commentary, she referred to the attacks as a "monstrous dose of reality" and criticized U.S. public officials and media commentators for trying to convince the American public that "everything is O.K." Specifically, she opposed the prevalent belief that the perpetrators were "cowards" and argued the country should see the terrorists' actions not as "a 'cowardly' attack on 'civilization' or 'liberty' or 'humanity' or 'the free world' but an attack on the world's self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a Consequence of specific American alliances and actions".

Sontag continued to theorize about the role of photography in real life in her essay "Looking at War: Photography's View of Devastation and Death", which appeared in the December 9, 2002 issue of The New Yorker. There she concludes that the Problem of our reliance on images and especially photographic images is not that "people remember through photographs but that they remember only the photographs ... that the photographic image eclipses other forms of understanding—and remembering. ... To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture" (p. 94).

Sontag died in New York City on 28 December 2004, aged 71, from complications of myelodysplastic syndrome which had evolved into acute myelogenous leukemia. She is buried in Paris at Cimetière du Montparnasse. Her final illness has been chronicled by her son, David Rieff.

A documentary about Sontag directed by Nancy Kates, titled Regarding Susan Sontag, was released in 2014. It received the Special Jury Mention for Best Documentary Feature at the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival.